We recently presented a poster at the ISMB 2024 conference in Montreal!

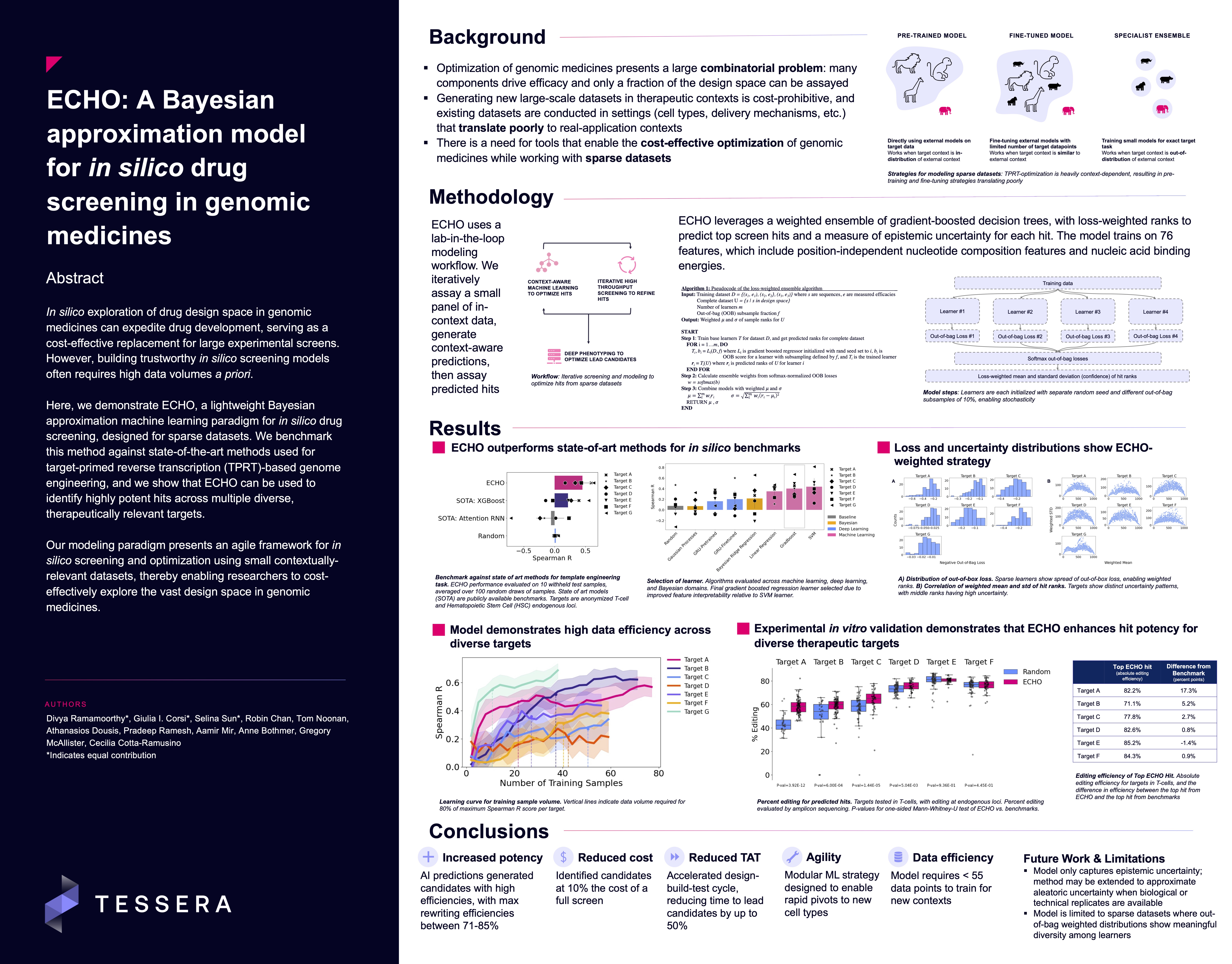

Project Overview

In this project, we worked on optimizing RNA sequences for Tessera’s genomic medicines. In doing so, we faced a problem that is common to biological settings: we needed a way to cost-effectively predict which sequences would have the highest potency, and we only had the capacity to screen a small number of samples. In addition to predicting which sequences would have highest potency, we wanted a measure of how confident we were in each prediction; we used this uncertainty to help us decide which hits to screen.

We evaluated several approaches for this task. Standard Bayesian models like Gaussian processes are useful for estimating uncertainty; they allow you to guess what an output may look like (a prior distribution) and update that distribution based on your collected data (a posterior distribution). However, we quickly realized that in our case, because we did not have a strong prior and had sparse data, this class of Bayesian models tended to overfit, leading to poor model performance.

We also evaluated deep learning approaches involving transfer learning and fine-tuning. We had access to large public datasets that shared some properties of our problem. We evaluated if we were able to train a model on this publicly available data and update the model (fine-tune) on our internal data. The success of fine-tuning approaches often depends on how much your final use-case is related to the data the model was originally trained on. In our case, we found that available data was too different (out of distribution) even after fine-tuning, leading us to methods that were a better fit for the sparse in-house data we had available.

We ended up going with one of our simplest model classes: ensembles! Ensembles are one of the oldest tricks in the book – they leverage the fact that training many models (where each model is called a learner) and aggregating them can lead to better performance than training just one model. Here, we use a specific case of ensembling: we induced stochasticity in our models through random parameter initializations. We added a couple of tricks to standard ensembling that helped our model, including using out-of-bag losses as a measure of learner generalizability and loss-weighting each of our learners when approximating the uncertainty of our final hits.

Together, these helped us get to a lightweight and robust model – and we were excited that when we experimentally tested our predictions, we saw improvements in the potency of our genomic medicines across diverse therapeutic targets!

If you’re curious about learning more, check out our poster below and presentation!

Poster